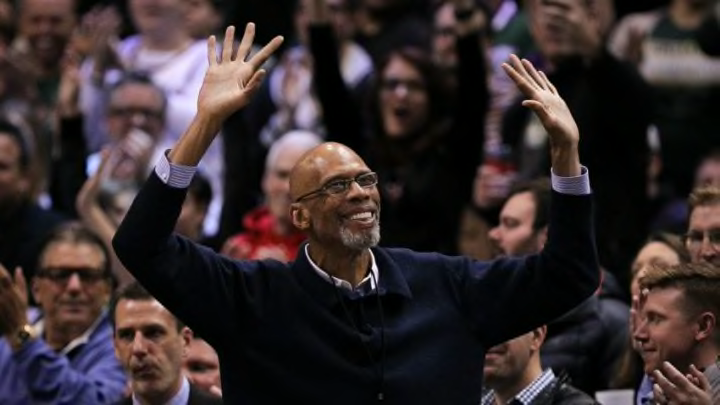

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar changed everything for the Milwaukee Bucks upon his arrival in 1969 and opposing teams were determined to slow down his and Milwaukee’s pursuit of a dynastic run in the early 1970s.

From the moment Kareem Abdul-Jabbar entered the NBA and became the centerpiece of the Milwaukee Bucks, he was unsurprisingly viewed as the next big thing.

Abdul-Jabbar stood as the figurehead for the next wave of supremely skilled, athletic big men that graced the NBA throughout the 1970s. The legendary centers in the 1960s, players like Bill Russell or Wilt Chamberlain, were either on the verge of retiring or firmly in the twilight of their careers and Abdul-Jabbar was set to ascend over contemparies such as Willis Reed and Nate Thurmond.

More from Bucks History

- The 3 biggest “What Ifs” in Milwaukee Bucks’ franchise history

- 6 Underrated Milwaukee Bucks of the Giannis Antetokounmpo era

- Ranking Giannis Antetokounmpo’s 10 best Bucks teammates of all time

- How well do you know the Milwaukee Bucks’ top 20 career point leaders?

- Looking at important playoff numbers in Milwaukee Bucks franchise history

Standing at 7’2″ and a svelte 230 pounds, Abdul-Jabbar’s mix of size, mobility and quickness, ball handling, and shooting touch made him a multi-faceted weapon that still stands unrivaled throughout the history of the league.

With that, though, Abdul-Jabbar became the main bullet point of all scouting reports for opposing teams as they looked to slow down the Bucks in any way they could.

At 22 years old entering the NBA, Abdul-Jabbar was already adept at the attention and ways his talent and physical stature would be exploited by the opposition. I mean, the NCAA literally banned dunking for the final two seasons playing for UCLA solely due to Abdul-Jabbar and his towering stature.

But as his teammate and Bucks guard Freddie Crawford explained to Sports Illustrated’s Tex Maule during Abdul-Jabbar’s rookie season in 1969-70, banning the dunk as the NCAA did may have opened up Abdul-Jabbar’s shooting abilities to truly fortify his vast, all-encompassing skill set:

"“He may be the first of the 7-foot backcourt men,” says his teammate, Fred Crawford. “He can dribble and make moves that no big man ever made before. Russell could dribble straight down the floor, but Lew can bring the ball down and handle it and give you fakes, and no one his size could ever do that.“If all Lew had to do was play defense, he could do it as well as Russell. He has all Bill’s quickness and he’s much taller. Offensively, he’s a better shot than Chamberlain and he moves. Wilt used to go into the post and lean on people, and when he leaned you couldn’t do much about it. Lew’s not that strong, but he can put the ball down and beat you with speed and agility, and Chamberlain couldn’t do that. And he has more shots than Wilt. I think that banning the dunk when he was in college may have been the best thing that happened to him. It took away an easy shot for him, but it made him learn other shots, and now he’s a versatile shooter. And in the pros he can still dunk the ball.”"

Simply put, there was no way of stopping Abdul-Jabbar on his own, given his otherworldly talents. And the rest of the NBA quickly realized that, especially as the supporting cast around him, whether it was trading for Oscar Robertson, the emergence of forward Bob Dandridge and so on, made Abdul-Jabbar that much more dominant.

Strategies varied from team to team and coach to coach as the NBA evaluated and toyed with multiple ways to try and throw the Bucks off their path of winning multiple 60-win seasons and two NBA Finals trips in four years from 1971 to 1974.

Take this sampling of coaches’ opinions at the time, ranging from Bob Cousy and Tommy Heinsohn to Bill Sharman, Dr. Jack Ramsay and Gene Shue, as Sports Illustrated dug into trying to defend against the Bucks and Abdul-Jabbar back in November of 1971:

"“I don’t know whether it’s worth going into,” says Cousy of the Cincinnati approach to playing Jabbar. “You kind of play it by ear. We alternate double teaming on him. One quarter we’ll send a double team in from behind. Another quarter from the front. I guess you could say we alternate strategy and get down on our knees and pray. There’s just not a lot you can do.”“To play the Bucks effectively you have to make adjustments,” agrees Celtic Coach Tom Heinsohn, whose team is the only one to beat the Bucks this year. “Jabbar’s secret is that he is 7’4″ and very smart. When you try to double-team him, he picks it up in a jiffy.”“I think you have to have a running game and sustain it,” says the Lakers’ Sharman. “If you let Milwaukee set up with Jabbar in the middle, those little quick forwards will pressure you up tight.”“We try to penetrate against them,” says Philadelphia’s Jack Ramsay.“My approach to beating Milwaukee is to concede that Jabbar will score, and make him the sole responsibility of one player, Wes Unseld,” explains Bullet Coach Gene Shue. “I’d plan to control the other four guys. New York did that well last year.”"

Playing in an era where there was no 3-point line and zone defenses were deemed illegal unlike today’s game serve as distinct differences. But the tactic of slowing the Bucks down, throwing multiple bodies towards Abdul-Jabbar’s way and forcing his teammates to taking advantage gradually grew into favor as his stint went on.

Tom Nissalke, a Bucks assistant coach under Larry Costello from the expansion season to the 1971 title-winning year, dished on that very blueprint once he left for the ABA in that same piece by Sports Illustrated:

"“I’d also sag in on them and concede the outside shot. If you sag in, Kareem will throw it back outside and you’ve got some hope. The Bucks shot over 50% last year, which was a record, because teams allowed them to get the break and shoot inside. And the thing you’ve got to stop at all costs is letting Jabbar roll into the middle for his skyhook. Block him—let him do anything—but don’t let him have that shot."

The Bucks certainly had a supporting cast that could knock down shots from outside between Robertson, Dandridge, the sharpshooting Jon McGlocklin and eventually Lucius Allen to deflect the attention that entered Abdul-Jabbar’s orbit. The same stood for being able to service the ball into the low post for Abdul-Jabbar, as well as the former Bruin’s ability to pick out teammates cutting to the basket to combat any double teaming that he faced from the opposition.

But the relentless pressure that Abdul-Jabbar increasingly faced as the Bucks’ run went on in the early 1970s and the injuries that significantly hampered Allen, McGlocklin and Robertson eroded the core around Abdul-Jabbar and opened up the opportunity for opponents to make the Bucks’ supporting players beat them.

Certainly, Game 7 of the 1974 NBA Finals stands as the defining display of the ‘Kareem rules’ being enforced.

Boston’s famous full-court pressing defense under head coach Tommy Heinsohn had harassed and exhausted Bucks ball handlers all series long, but Abdul-Jabbar still feasted to that point in the Finals and lead a less than full strength Milwaukee club.

It was following Abdul-Jabbar’s miraculous skyhook to win Game 6 in double overtime that forced Heinsohn to veer away from their established defense, as he ultimately opted to double Abdul-Jabbar the moment he caught the ball, forcing others to step up in the decisive Game 7 in Milwaukee.

The idea of doubling Abdul-Jabbar was something that Heinsohn purposely avoided before he had a conversation with Cousy that came about following Game 6 as Jim Owczarski of On Milwaukee recounted back in June of 2014:

"“Not because I believe the strategy will work,” Heinsohn clarified. “But because I think it will cause a surprise and it will take a while for them to adjust, and maybe we can take the crowd out of the game in the first quarter.”Heinsohn was about to toss his defense out the window with no practice, shootaround or walkthrough to implement the new one. Despite the fact he had eight championship rings of his own as a player and 258 wins as a coach, he was nervous.“If it didn’t work I might have been out of a job,” Heinsohn said. “Because the press being what it was – could a coach expect to change an entire defense in one day and play for the championship? What is he crazy? That’s the type of thing you were facing making a decision like that in one day.”"

The pivotal adjustment flummoxed Abdul-Jabbar and the unsuspecting Bucks players that were thrust to deliver in roles they were unfamiliar with. Poor Bucks forward Cornell Warner was exploited by the Celtics’ defensive tactic and Robertson didn’t, uh, mince words about his play in the final game of that series in the aforementioned On Milwaukee piece:

"“We had a forward who didn’t even hardly score, or hardly play, so you call timeout and you try to get adjustments made – it’s up to the coach to make the final decision,” Robertson said. “Cornell Warner could not have been the hero of that situation because we didn’t call on Cornell Warner to shoot the whole year, so why would we put all that pressure on him then? We should’ve put a shooter over there.”"

In that 102-87 Game 7 loss, Abdul-Jabbar finished with 26 points on 10-of-21 shooting (6-for-11 from the foul line), 13 rebounds and four assists.

Abdul-Jabbar went on to overcome the pressure of relentless defensive tactics and pressure in future NBA Finals trips and championships runs with the Los Angeles Lakers. And it certainly helped that the Lakers eventually boasted a stronger supporting cast than the Bucks could offer during his six seasons in Milwaukee.

However, it’s a testament to Abdul-Jabbar’s greatness that he was able to rise above it time and time again and have the remarkable career and longevity he enjoyed throughout his 20-year NBA career.