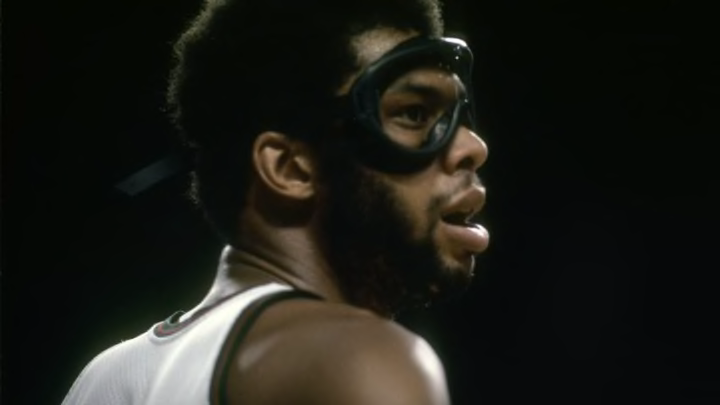

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar performed at historic levels during his time with the Milwaukee Bucks, in spite of significant challenges in his life off the court.

To this day, Milwaukee Bucks fans will have mixed feelings about the grounds used by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar to force a trade to the Los Angeles Lakers, but the sentiment behind it was just a brief peek behind the curtain of what was a complicated life for the greatest player ever to suit up for the franchise.

As Wayne Embry, then the general manager of the Bucks, recalled years later:

"“We asked Kareem if there was dissatisfaction with us and he said, no, he just wanted to be traded from Milwaukee. He said his life style and the life style in Milwaukee were not compatible.”"

More from Bucks History

- The 3 biggest “What Ifs” in Milwaukee Bucks’ franchise history

- 6 Underrated Milwaukee Bucks of the Giannis Antetokounmpo era

- Ranking Giannis Antetokounmpo’s 10 best Bucks teammates of all time

- How well do you know the Milwaukee Bucks’ top 20 career point leaders?

- Looking at important playoff numbers in Milwaukee Bucks franchise history

It’s widely known that having been drafted by the Bucks as Lew Alcindor, the former UCLA Bruin changed his name to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar in 1971. In spite of having started to study the Qur’an during his time in college, this marked Abdul-Jabbar’s official conversion to Islam in the eyes of the wider public.

As Abdul-Jabbar explained in an op-ed for Al Jazeera in 2015, the decision signalled something of much greater personal and spiritual significance to him, though.

"“I came to realize that the Lew Alcindor everyone was cheering wasn’t really the person they imagined. They wanted me to be the clean-cut example of racial equality. The poster boy for how anybody from any background — regardless of race, religion or economic standing — could achieve the American dream. To them, I was the living proof that racism was a myth.I knew better. Being 7-foot-2 and athletic got me there, not a level playing field of equal opportunity.”"

He continued:

"“The adoption of a new name was an extension of my rejection of all things in my life that related to the enslavement of my family and people. Alcindor was a French planter in the West Indies who owned my ancestors. My forebears were Yoruba people, from present day Nigeria. Keeping the name of my family’s slave master seemed somehow to dishonor them. His name felt like a branded scar of shame.”"

In short, Abdul-Jabbar was going through a journey of personal discovery, and a battle to carve out his own identity. Lew Alcindor was one way in which he could be pigeon-holed. Being the best basketball player on the planet was, in many ways, another.

While Abdul-Jabbar continued to pursue his own journey of spiritual emboldenment, creating greater space for spiritual and personal influencers around him, he was still performing at levels that have arguably not been matched to this day.

Kareem’s place in the pantheon of all-time greats is appropriately complicated, as so many of the most dominant figures who came after him were smaller, quicker, and often playing what resembled a different game. For example, debating whether Kareem had a greater influence on his teams than Michael Jordan or LeBron James had on theirs isn’t necessarily going to yield easy answers.

What is indisputable, though, is that Kareem was a master of his own element. Abdul-Jabbar was able to hone and maximize his considerable skills and physical gifts in a way that many others have not come close to. It may have been just a single weapon in his arsenal, but his patented sky-hook stands out as an obvious example of that.

During his six full seasons in Milwaukee, Abdul-Jabbar averaged 30.4 points, 15.3 rebounds, 4.3 assists, 3.4 blocks and 1.2 steals per game, while shooting 54.7 percent from the field.

The Bucks played through that era with a remarkable record of 342-124 (.733), yet in many ways they underachieved. Considering their regular season performances and the embarrassment of riches their roster boasted, they could have had so much more than just two trips to The Finals and a single championship success.

On the other hand, there’s a case to be made that it’s a marvel that the Bucks and Kareem, individually, managed to perform at such a high level considering much of the distraction that surrounded them away from the court.

Having initially been a figure on the outside whose life view was changed by observing the injustices suffered by African Americans and Islamic groupings in the U.S., Kareem’s status as a public figure eventually drew him into the center of those stories as his time in Milwaukee drew on.

In the early stages of his learning in Islam, Abdul-Jabbar had befriended Hamaas Abdul Khaalis, a leader of a school of Hanafi Muslims. As a part of their relationship, Abdul-Jabbar donated a house in Washington D.C. to Abdul Khaalis and his followers. In 1973, that detail brought Abdul-Jabbar a brand of attention that he certainly wouldn’t have anticipated.

Following disparaging letters from Abdul Khaalis about Elijah Muhammad, the leader of the Nation of Islam, a group of men connected to the Black Mafia in Philadelphia murdered seven members of Abdul Khaalis’ family, including five children, at the house purchased by Kareem.

In the years that followed, Abdul-Jabbar distanced himself from Abdul Khaalis, whose actions became more radical before ultimately resulting in the Hanafi Siege in 1977. Still, with the connection between the two men already established, Kareem’s life changed dramatically.

As Bucks teammates of his recalled in the HBO documentary, Kareem: Minority of One, with Abdul-Jabbar viewed as a potential target for an attack, the team was not just accompanied everywhere by personal security and local law enforcement, but also FBI agents.

Peter Carry of Sports Illustrated detailed the strange environment which Kareem and the Bucks found themselves in for a 1973 cover story, entitled “Center in a Storm”.

"“Returning from a road trip one afternoon last week, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar deplaned, took a few quick steps across the apron at Milwaukee’s Mitchell Field, climbed the stairs into the terminal and headed down the concourse accompanied by a man wearing a fur-collared beige car coat and charcoal trousers. Abdul-Jabbar’s companion was of medium height and medium build and had medium brown hair turning to gray; what was distinctive about him was his shoes. They were black and had unfashionably thick rubber soles that protruded perhaps half an inch all around. They were the footwear of his profession, and identified him as clearly as the badge in his pocket. The man was a cop.Specifically, he was a detective from the Milwaukee Police Department and, like plainclothesmen in Chicago and Detroit, he has recently served as a bodyguard for the Bucks’ center. It is a job he performs amicably and one Abdul-Jabbar accepts with good humor, surprisingly so since the mere presence of the detective unavoidably reminds him of the horrible events that led to the protection.”"

In that same piece, Carry outlines how drug charges brought against guard Lucius Allen and a team-imposed suspension on guard Wali Jones for “conduct detrimental to basketball”, had made for even greater challenges as the Bucks attempted to retain their focus on the NBA season.

Speaking to Carry about his great friend and teammate, Kareem, Lucius Allen made a remarkable proclamation about the events of the Washington D.C. murders and the scrutiny that came in the aftermath:

"“I can sense that it bothers him,” Allen says. “He carries it around within him. But it’s not there on the court. At no time is it on the court.”"

The team’s record throughout those years backs that sentiment up, but with hindsight it’s almost impossible not to question if the toll of all of that emotional baggage weighed down the team at the end of the year. It’s one thing to carry such incredible challenges throughout the regular season, but after 82 games, having to power through the physical and mental fatigue in the playoffs may just have been one step too far.

For example, after a 60-win season in 1973, the Bucks crashed out to the Warriors in their opening series of the playoffs. The only other occasion during Kareem’s tenure when the Bucks failed to make at least their Division/Conference Finals was his final season, where injuries disrupted Abdul-Jabbar and the team, and his mind was clearly already in Los Angeles.

The body of work that Kareem compiled during his stint in Milwaukee grows all the more legendary when the events he was dealing with off the court are taken into consideration.

Abdul-Jabbar was a pall-bearer at the funeral of the seven victims of the 1973 massacre, and as he later went on to comment:

"“They were like my family, like seven brothers and sisters”."

For those who weren’t there, there’d be no justice in passing judgement on Kareem for the decisions he made at that time. His actions and relationships were faith-based, and if not for fame, he would have remained an anonymous peripheral figure in the discourse that followed.

From the basketball perspective, it’s impossible not to wonder what could have been in those Milwaukee years, for an astonishing player and the legitimately great team he played on, if things had just been a little bit more serene off-the-court.

Life is rarely serene or straight forward, though, and the world around us doesn’t often oblige in making things easier. If ever proof was needed of that, Kareem’s life and career in the NBA can act as a testament to it.